Live Art Sector Research – A Report Mapping the UK Live Art Sector is the first ever survey of the sector’s impact and influence. It will help readers to identify ways to support artists and organisations who work with a range of ambitious experimental, process-based, and participatory practices.

Live Art in the UK came of age in the late twentieth century and has grown from strength to strength in the twenty-first century.

Today, Live Art practice spans a wide range of disciplines and artforms; is located in all kinds of traditional, unconventional and permissive cultural contexts; and is engaged in the most urgent critical discourses about the nature, role and responsibility of art and of artists. Live Art proposes new ways of thinking about, making, presenting, and encountering art. It foregrounds embodied and experiential practices; it creates space for underrepresented identities, issues and ideas to be seen and heard; it welcomes collaboration, interaction and participation; it embraces dissent, difference and difficulty; and it invites debate about who we are and the relations between peoples and places. In this questioning of what art can be, where it can be, who it can be, and what it can do, Live Art can be understood as a research engine of culture.

Andy Field (founder of Live Art organisation Forest Fringe) once said that Live Art is simultaneously ubiquitous and elusive. Although its presence can now be found in so many aspects of UK cultural life, Live Art’s absence is still felt within dominant cultural narratives and in traditional art histories, critical debates, institutional contexts and funding programmes. This might partly be because Live Art is still a relatively new and unquantified sector. There had never been a comprehensive review of Live Art’s achievements, nor an extensive analysis of its impact and influence.

Whilst recognising that much Live Art rejects dominant narratives and might not crave institutional approval or mainstream embrace, many working within the sector, and particularly members of the Live Art UK network, increasingly felt the need to redress this. We believed that there was an imperative for an in-depth investigation into the conditions in which Live Art exists to better understand the potential and challenges of its expanding parameters and reach, and to advocate for more awareness, support and investment in such ways of thinking and doing for the future. We were excited that Arts Council England backed our ambition to review Live Art, and particularly in relation to its own priorities and principles, and, with their support and guidance, the Live Art Development Agency, in partnership with Live Art UK, commissioned this unprecedented independent research project.

Live Art Sector Research – A Report Mapping the UK Live Art Sector was undertaken by an exceptional collective of independent artists, researchers, thinkers, producers and activists. Their research began in Autumn 2019, but was paused in Spring 2020 when it became clear that the project must reflect and act in response to the immediate and lasting impacts of the unfolding events of 2020: the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic, the renewed calls for racial justice by the Black Lives Matter movement, and the fallout from Brexit. We are indebted to the research team for so adeptly incorporating these urgent revisions in their process and plans, and to Arts Council England for offering additional support to enable this.

Live Art Sector Research – A Report Mapping the UK Live Art Sector is an extensive, expansive and hugely significant piece of research. It has been realised through surveys, focus groups, literature reviews, case studies, and interviews, and the privileging of artists’ voices through a collection of ‘Perspectives‘ and the commissioning of artworks and writings that complement and contextualise the research’s findings. It offers the first major overview of the landscape of Live Art, how it thinks and operates besides, within, and in relation to wider culture and to society, and the vital contributions it makes to so many lives.

Live Art Sector Research – A Report Mapping the UK Live Art Sector profiles Live Art’s resourcefulness and inventiveness; its capacity to engage with complexity and risk, to offer alternative approaches to art making, activism and community building, to provide safe spaces for dangerous ideas; its critical relationship with higher education; and the key role that artists and artist-led initiatives play in driving the sector.

Its findings and opportunities for action also address the challenges facing the sector, and challenges within the sector in relation to racial equity, inclusion and representation, to issues of critical care and labour practices for artists and arts workers, to the need to engage with publics and places beyond metropolitan centres, and to Live Art’s responsibilities to our communities and our environments.

Our intention is that Live Art Sector Research – A Report Mapping the UK Live Art Sector will act as a useful and generative tool for those working with Live Art, and for policymakers, funding bodies, programmers and producers, educators, and everyone concerned with what innovative, experimental and experiential artistic practices can be and do. Live Art Sector Research – A Report Mapping the UK Live Art Sector also presents one of the first opportunities for the cultural sector to look at the impact of the seismic events of 2020 and to consider the strategies and fresh thinking we need to respond to this cultural moment in order to move forward and create the futures we all want to see.

Live Art Development Agency and Live Art UK

June 2021

At its best, Live Art is rigorous, irreverent, brave and kind of… exhilarating! Because it’s space. Space on the margins to imagine different ways of living, and to truly create and exercise agency… where life and art are inseparable and shape one another.1

Selina Thompson, artist

Live Art Sector Research – A Report Mapping the UK Live Art Sector is the first ever UK-wide research project into the Live Art sector, funded by Arts Council England and commissioned by the Live Art Development Agency in partnership with Live Art UK. It maps the Live Art sector, its impact and influence in order to identify the best way to support artists and organisations who work with a range of ambitious experimental, process-based, socially-engaged and participatory practices.

The following questions were agreed with Arts Council England at the outset of the research project and underpin our approach to researching sectoral activity:

The project’s research activities took place between September 2019 and May 2021 and its methodologies included:

This report is intended to be read by artists, organisations, funders, policymakers and researchers, in the Live Art sector and beyond, with an interest in the ongoing development of innovative artistic practices, and the celebration of everyone’s creativity and diversity – all key components of Arts Council England’s ‘Let’s Create, Our Strategy 2020–2030’.3 The report provides findings and opportunities for action that support and inform delivery of a range of UK arts and culture funding frameworks, including Arts Council England’s Let’s Create.4 It addresses how sectoral support for Live Art practices in the UK contributes to strategic areas and priorities, including ambition and quality, inclusion and relevance, creativity, and new approaches to collaboration and participation.

Through our research, we have found that the UK Live Art sector comprises a diverse ecology of projects, groups, initiatives and organisations of different scales, sizes and remits, each making a significant contribution to the development of Live Art practices. Live Art practices are wide-ranging and projects are often ambitious, offering opportunities for audiences to encounter work in a variety of spaces: from galleries and theatre spaces to clubs and community centres. The Live Art sector supports practices that experiment with audiences, develop and enrich civic relationships, and feed into how arts organisations work with young people.

People working in the Live Art sector are extremely skilled, resourceful and committed. However, our research reveals that whilst practitioners working within the Live Art sector are adaptable and resilient, a culture of underpaid work takes its toll on practitioners, financially and emotionally. Over the last twenty years, the Live Art sector has cultivated a productive relationship with higher education, in terms of visibility and cross subsidy, which now faces increasing resourcing challenges.

Our research has found that the Live Art sector nurtures a broad spectrum of ideas of practices, and that it promotes cross-pollination and collaboration between itself and other sectors. The UK Live Art sector has regional, national and international reach. It is well placed to make important contributions to new aspects of participatory and collaborative practice. Live Art promotes ongoing experimentation into the complex relationship between audience and live encounter, offering other sectors and creative disciplines innovative ways of understanding how publics experience art and creativity.

The UK Live Art sector supports artistic practices that impact and influence wider culture and society. Although Live Art encompasses a wide range of approaches, the term Live Art is not always used by practitioners and publics. Live Art tests and challenges limits across artforms, cultural conventions and social practices which correspond with the sector’s imagining of itself as a space of cultural resistance, manoeuvring between grassroots activity and visibility in mainstream spaces. The sector has demonstrated its capacity to thoughtfully and actively respond to the most serious challenges facing contemporary society brought about by the climate crisis and structural inequalities. The Live Art sector is diverse, yet like all areas in the arts and cultural sector, it could do more to nurture diverse talent and leadership.

Supporting Live Art can – and does – benefit artists and artform development. Investment in the celebration of everyone’s creativity and the development of creative and critical thinking would be well supported through the Live Art sector.

We open this report with a statement on our positionality as researchers and project managers of this research on the Live Art sector in the UK, in order to offer our intentions, motivations and transparency about how we are, as a research collective, intertwined in the workings of the sector itself.

Dr Cecilia Wee (co-lead of the research collective) is an independent curator, educator and researcher based in London. She is a second generation South East Asian cis-gendered woman.

Dr Elyssa Livergant (co-lead of the research collective) is an artist, researcher and educator based in London. She is a white, queer, cis-gendered woman from a middle class background.

Chinasa Vivian Ezugha is a Nigerian-born artist, researcher and cultural worker based in Hampshire.

Dr Johanna Linsley is an artist, researcher and lecturer based in Dundee, Scotland. She is a white, queer, cis-gendered woman. She is a citizen of the United States and in full-time employment in higher education.

Dr Tarek Virani is Associate Professor of Creative Industries at UWE Bristol based in South West England.

Dr Tim Jeeves is an independent artist and city councillor based in Liverpool. He is disabled, white, British, cis-gendered and male.

The research collective is primarily composed of people who have worked in the Live Art sector in roles such as researchers, teachers, artists, curators, board members and arts workers. Between us, our professional engagement with the sector can be traced back to 2004. We acknowledge and recognise how our involvement with the sector, both in our individual and collective work, has had and may continue to have potential for reproducing racial, class, ableist and gender inequities that exist in both the Live Art sector, the arts sector and society more broadly. In an effort to be as inclusive and representative as possible, we have worked with a diversity of practitioners, including a research advisory group convened by Live Art Development Agency (LADA), who represent a spectrum of identities.

Our approach to this report, which brings our perspectives of working within and outside Live Art in different locations across the UK, is to create a rigorous, critical and robust research base that maps the impact and influence of Live Art, both problematising and celebrating its complexity, diversity, and achievements, and generating fresh thinking about potential opportunities for the sector. We also acknowledge that Live Art is embedded in the current social, economic and political contexts of its time and therefore is subject to the material and ideological dynamics that produce injustice and domination.

Informed by our various experiences of diversity and representation, artist development and experimentation, and the effects of Live Art on the wider cultural sector, we have approached this review with curiosity, criticality and hope for the future. We are motivated by a spirit of intellectual and creative enquiry and an ethical commitment to social justice. We are committed to producing research with social and cultural impact, particularly for: artists; arts agencies and organisations; policymakers; and individuals from marginalised communities. Moreover, by creating spaces to explore relationships between grassroots practices and institutional powers, our approach is reflective of dialogic ways of working that are fundamental to Live Art.

This is a collective report, but Dr Elyssa Livergant and Dr Cecilia Wee have been leading the research, both in terms of steering the process and direction, as well as spending more time and labour on its production.

When we began this report in Autumn 2019, the arts and cultural sector was already experiencing a great deal of pressure from the fallouts of a long period of austerity5. In the interim period, COVID-19, Brexit6, and renewed calls for racial justice by the Black Lives Matter movement have intensified the multiple challenges facing Live Art and the wider arts and cultural sector. Even now, at the time of writing, the sector faces tremendous uncertainty, with staff from organisations on furlough and an ongoing lack of government financial support programmes for freelancers (including artists) since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. These circumstances are layered upon the already precarious nature of independent labour within the Live Art sector.

Given the significance of these challenges and the complexity of these issues, we advocate not only for sustaining the practice of Live Art, but moreover, we advocate for sustaining the welfare and nurturing of people who are currently involved in the UK’s Live Art sector, as well as those who may find a home in Live Art in the future.

This research project and subsequent report is the first of its kind to map the Live Art sector in the UK. It has arisen from lobbying activities undertaken by the Live Art Development Agency (LADA) and the 30 organisations across the nations making up the Live Art UK network over the last decade, including: In 2010, LADA and Live Art UK instigated In Time, a series of case studies about Live Art’s diversity and impact7. LADA, with the support of Live Art UK, initiated the first ever cross-department meeting at Arts Council England about Live Art and the contributions it makes to culture and to artform development8. In 2018, the Live Art UK network began discussions with Arts Council England to request a nationwide sector review. This continuing dialogue was also informed by the 2019 publication of It’s Time by LADA, Wunderbar and partner organisations, which presented a series of contextualising essays outlining both the robustness of performance-based art in the UK and the increasingly fragile conditions that the sector and artists working with Live Art were facing9.

In Spring 2019, Arts Council England funded LADA, working in partnership with Live Art UK, to undertake research into the current conditions, opportunities, challenges and impacts of the Live Art sector in England. LADA decided to commission independent consultants to undertake this work and to expand the remit of the project to the UK. Following a call for proposals from LADA, our research collective was awarded the commission to undertake this research, which was to run from September 2019 until June 2020. Following a pause in activities in response to COVID-19, the review period was extended until June 2021.

We were tasked with producing a report that would be relevant to a range of audiences that include the Live Art sector, funders, local and national government and higher education and wider sectors. Further, part of the brief for this project was to contribute to future directions and developments in policy and provision for the sector, as well as identifying opportunities for action in relation to future funding and economic models for Live Art.

This research was designed to address the following objectives:

Principles and ethics of our approach

Our collaborative, action-research-oriented approach as a research collective situated across the UK aims to collect and represent as full a scope of practices and geographies as possible within the confines of the project. We have chosen an action-research approach, which is participatory and historicised, because it foregrounds working in partnership and collaboration with communities at the core of research to collectively define and co-produce change. 10

Scope of the research

This study was designed to map the Live Art sector in the UK, and involved participation of artists, independent arts workers, educators, organisations, funders and arts councils working across all regions and nations of the UK. This process and the ongoing pressures on the arts and cultural sector since the COVID-19 pandemic threw into relief some challenges for the scope of our research. The relative instability of the term ‘Live Art’, and its limited currency for artists, arts workers, organisations and funders was noticeable, especially in Northern Ireland and Wales. This contributed to the lack of uptake for focus group participation and responses to our 2019 survey of individuals in these nations. We addressed this by drawing on broader knowledge of our research advisory group and Live Art UK members, who put us in direct contact with artists and organisations in Northern Ireland and Wales. We also drew on desk research, themed roundtable discussions on higher education, and individual consultations with artists, educators and organisations in Wales and Northern Ireland.

However, there is more work to be done. As noted in Part 1, Section Three: Addressing the Term, we anticipate two upcoming studies will offer helpful insights and add to a further detailed mapping of the sector: Stephen Greer’s ‘Live Art in Scotland’, an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project investigating the history of Live Art in Scotland that launched in 2021, and the upcoming PhD project ‘Performance Art in Northern Ireland’ beginning in September 2021, undertaken by artist and Bbeyond co-founder Brian Patterson at Ulster University. A comparison of experience and participation in activity across England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland11 in relation to specific social, economic and political contexts could enable a further nuanced analysis of the unique characteristics of the UK Live Art sector.

As this is the first type of research on the Live Art sector in the UK to include the collection of quantitative data, there are gaps in our report. We draw on publicly accessible data from all UK arts councils and have been granted access to specific data about Live Art and live performance project funding and National Portfolio Organisations from Arts Council England. The scope of our study was limited in the degree of detail it could collect, for example on working conditions and pay. Equally, we have not provided an intersectional analysis of the sector’s workforce. We have addressed these limits through drawing on workforce analysis from relevant and related artform sectors. However, a piece of future research focused specifically on a Live Art sector workforce review would certainly help to address these gaps.

Research phases

This project had two phases:

Phase 1: Mapping the Live Art sector, including focus groups and a survey for individuals in the sector (October 2019–March 2020).

Phase 2: Research roundtables, dialogue sessions, an organisational questionnaire and reappraisals of Phase 1 findings in the context of emerging research in the wake of COVID-19, Brexit and the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement (October 2020–May 2021).

Throughout both phases we have worked in dialogue with LADA, Live Art UK and Arts Council England. Our research has been supported by an advisory group organised by LADA and composed of artists, organisations, programmers, academics and funders working with Live Art across the UK. A list of research advisory group members can be found in Appendix I.

2019 survey of individuals

The 2019 survey of individuals working in the Live Art sector included topics such as: artform and discipline; collaborations; audience; Live Art as a category of practice and sector; engagement with networks, platforms and support systems; funding and resources; and demographic details. The survey comprised forty-five questions, enabling us to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. It provides a unique snapshot of the UK’s Live Art sector between November 2019 and February 2020.

Survey themes were identified by the research collective, with support from the Artist Perspectives roundtable in October 2019. The survey was delivered online via Survey Monkey and shared through Live Art UK, its partner organisations’ mailing lists and via social media. We provided access support for respondents who needed this to complete the survey. The survey was anonymous in that respondents were not asked to identify themselves or their affiliations. Where such personally identifying information was provided, we have removed this from inclusion in this report.

The 2019 survey of individuals was created to capture insights from people working across the sector – both independent workers and those employed in venues and institutions – about their work with Live Art, the economic conditions of the sector and what they value about Live Art. We received 258 responses to the survey, an extremely robust response rate which provided a statistically significant sample of data from which to work. 12There is no sturdy estimate of the size of the Live Art workforce in the UK. Therefore, data from our survey is presented based on unweighted (raw) data and is not compared to a total number of individuals in the sector.

Data from the 2019 survey of individuals can be found in Appendix IV. 13

2021 organisational questionnaire

An organisational questionnaire, planned for Spring 2020, was postponed when the research project was paused in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A new organisational questionnaire was designed in January–February 2021 to gather details and experiences of organisations and groups working in Live Art in the UK. It addressed conditions and concerns of organisations pre- and post- March 2020. It was targeted at Live Art UK members, as well as groups, projects and organisations connected to the research project’s advisory group involved in making, producing, disseminating, and supporting Live Art.

The respondents to the questionnaire encompass organisations of all scales and types, from grassroots collectives to publicly-funded festivals and venues. The 2021 organisational questionnaire consisted of thirty-three questions, focused on issues of organisational infrastructure such as finance, wage, and employee information. The survey also included ten questions which invited free text reflections on the impacts of COVID-19, Brexit, and organisational responses to recent calls for anti-racist action.

The 2021 organisational questionnaire was open for responses online from March to May 2021. We received twenty-two responses to this questionnaire; the rich qualitative data has informed our understanding of how Live Art infrastructure operates and points to how it is adapting to the current moment.

According to the participation agreement made with respondents, the research collective has treated the data gathered confidentially. Due to the sample size and the nature of the responses to the 2021 organisational questionnaire, respondents may be identifiable and so the data is not shared in full as an Appendix to this report.

Case studies: audience development

Case studies of three projects by artists and organisations working with Live Art practitioners were compiled, in collaboration with Live Art UK organisations, to better understand how the Live Art sector supports audience development. Case studies drew on projects taking place in Yorkshire, London, and the South East as examples of collaboration with professionals across different sectors, performances for older people and young people’s programmes. Each project case study describes target audience and numbers, the audience recruitment process and further activities to maintain engagement.

Consultations: regional and national focus groups

Regional and national focus groups were key to collecting views on successes, opportunities, and the state of the sector from organisations and groups receiving core funding from the arts councils, non-funded organisations, artists, funders, and other stakeholders. Focus group sessions lasted three hours and were attended by a maximum number of twelve participants. Seventy-three people participated in our regional and national focus group sessions. Each group was facilitated by members of the research collective and participants were invited to continue their dialogues beyond the sessions. Focus groups were centred on the South East (Folkestone), Midlands (Birmingham), the North (Manchester and Newcastle), Scotland (Glasgow), the South West (Bristol), and London between October 2019 and February 2020. Whilst focus groups included participants from different locations within the regions, we note a concentration of voices from the cities in which focus groups took place.

Consultations: themed roundtables and dialogues

The research utilised ongoing roundtable discussions and dialogues to further garner a picture of the Live Art Sector in the UK. Roundtable research discussions centred on the following themes and were attended by relevant stakeholders throughout the UK: Artist Perspectives (September 2019); Diversity (February 2021); Higher Education (February 2021); and Arts Councils (June 2020 and April 2021)14. Fifty people participated in our themed roundtables.

In addition, formal and informal dialogues took place throughout the research period and engaged the research collective, cultural workers, artists, funders and programmers.

Throughout our primary research activities, we have used Chatham House rules.15 This means knowledge that is produced can be shared outside ‘the room’, but the words will not be attributed to an individual. Therefore, throughout our report we have refrained from attributing information from these research activities to individuals. This is intended to respect privacy within a relatively small arts sector.

A list of individuals consulted in regional and national focus groups, themed roundtables and dialogues can be found in Appendix III.

Perspectives

A series of nineteen ‘perspectives’ from artists, organisations and projects working with Live Art feature in Part 3 of this report. Each perspective serves as a standalone mini section, offering another snapshot of what Live Art is and how it works, from the viewpoint of practitioners and organisations in the sector. The premise for the perspectives developed out of conversations within the research collective about the relationship between arts policy, especially Arts Council England’s Let’s Create strategy, and the representation of Live Art practices within this research.

The perspectives were selected to illustrate the diversity of practices and practitioners working with Live Art across the regions and nations of the UK, and in relation to geography, class, race and ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation, age and experience. Practitioners were asked to respond to a set of questions exploring how Live Art as a strategy informs their work and approach to audiences, how the sector has supported them, and the relationship between Live Art and social change. Each response has been edited for length and clarity. The set of perspectives are preceded by a framing introduction which further outlines the approach we have taken.

*Please note that the ‘perspectives’ contained in the downloadable report are abridged versions of the perspectives found on this digital platform.

Desk research

We have drawn on a wide range of types of secondary research materials such as journal articles, research publications, statistical reports, qualitative and quantitative research reports, websites, and online databases. This secondary research has focused on UK sources, including research produced by UK government departments and the Office for National Statistics; arts and culture sector reports by organisations such as Creative & Cultural Skills, the Creative Industries Federation, the Audience Agency and arts councils across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

In addition, as this research is the first of its kind for the Live Art sector, we draw on existing arts sector specific reports and data about the visual arts, dance and theatre sectors to provide context for our findings and data sets. Data from the visual arts, dance and theatre sector is valuable for our research as those working with/in Live Art often also identify with visual arts, dance and/or theatre.16 This report is also informed by a bibliography of writing by artists, critical thinkers and researchers about Live Art, which has especially flourished in the last twenty years.

Research Outputs

This report is available online and distributed as a print publication. The print version of the report is downloadable from this website. The report is accompanied by commissioned work from a number of artists and writers to create a body of new texts and artworks that respond to, contextualise and complement the research project’s findings and opportunities for action. The commissioned artists are: Aaron Williamson, Anne Bean, Alexandrina Hemsley, and Jamal Gerald. The commissioned writers are: Annie Jael Kwan, Phoebe Patey Ferguson and An*dre Neely, and Tim Etchells.

Live Art, as a term and a sector, has been the subject of much celebration, critical discussion and debate in the UK over the last thirty years. Since its inception in 1999, the Live Art Development Agency (LADA) has been important in advocating for the use of the term to describe a range of experimental aesthetic practices that sit across a number of disciplines including visual art, dance, theatre, writing and sound art. With the support of LADA’s advocacy, first in London and then across England, the UK and internationally, Live Art has developed into a central and, to some degree, centralising term. Rather than a descriptor for a particular artform, LADA employs the term Live Art to describe ‘a cultural strategy to make space for experimental processes, experiential practices, and the bodies and identities that might otherwise be excluded from traditional contexts…. [Live Art is] a way of thinking about what art is, what it can do, and where and how it can be experienced…. always explor[ing] the possibilities of the live event and the ways we can experience it’.17

As an artistic category, Live Art has tended to not only embrace practices that are in between traditions but also bodies, identities and cultural values that challenge social and cultural norms and perceptions. Theatre and performance scholar Theron Schmidt’s 2019 edited collection Agency – A Partial History of Live Art, offers a range of perspectives on Live Art to mark the twentieth anniversary of the creation of LADA. As Schmidt points out in his book’s introduction, the term Live Art is not only relatively new, it also stands in for a diversity of practices and approaches:

As a relatively recent way of framing certain artistic practices within the UK contemporary art sector, Live Art is intentionally capacious in the range of practices it can include: body art, performances for the stage, cabaret, interactions in public, site-responsive work, invisible interventions, overtly political actions and many other ways of working. From its early usages as a term, its very breadth and inclusivity has been held up as a strength.18

However, artists, practitioners and organisations who work with Live Art often resist set definitions of the term. It is a contested category, in part, because the practices it seeks to contain cut across and challenge disciplinary boundaries. As such, Live Art, as a term and category of practice, can often obscure varied disciplinary, historical and institutional genealogies. Indeed, we noted that participants in our research use terms like performance art, contemporary performance, experimental theatre, and time-based media alongside or instead of Live Art. For example, in Wales and Northern Ireland, artists, institutions and funders recognise the term Live Art, but are more likely to use the term and category of performance art when describing experimental performance-based work.

There already exists a range of excellent academic sources offering accounts of the development of the term and category Live Art, and the ways it has been deployed historically by artists, institutions and policymakers.19 Dominic Johnson’s edited collection Critical Live Art: Contemporary Histories of Performance in the UK, and Maria Chatzichristodoulou’s edited collection Live Art in the UK: Contemporary Performances of Precarity, are rich resources exploring the term, category and practices of Live Art. The Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project, ‘What’s Welsh for Performance?’ led by theatre and performance scholar Heike Roms, offers an invaluably comprehensive account and archive of the emergence of performance art in Wales in the later twentieth century. 20 Andre Stitt’s forthcoming chapter on Welsh performance art between 2008 and 2018 is an important complementary resource for researchers interested in a more recent history of experimental performance activity in Wales.21 Áine Phillips’ Performance Art in Ireland: A History is an essential edited collection on performance art in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland that seeks to contribute to the evolution of Live Art in Ireland and beyond.22 At the time of writing, two important pieces of research into non-mainstream experimental performance-based practices have recently got underway: ‘Live Art in Scotland’ and ‘Performance Art in Northern Ireland’, as mentioned in Section Two: Brief and Methodology. We look forward to these pieces of research which will no doubt further the work of mapping the impact and influence of Live Art in the UK.

The breadth of research into the histories of contemporary experimental performance-based practice is indicative of the increasing impact and influence of Live Art practices in the UK and beyond. LADA’s collaboration with Tate Modern on the 2003 programme Live Culture, featuring a range of non-mainstream experimental practices and approaches that centred on the body, liveness and the encounter between audience and action, was a precursor for the inclusion and presentation of artists working with Live Art that are now visible in mainstream cultural institutions such as the Tanks at Tate Modern, the Whitworth Gallery in Manchester, the Royal Court Theatre and Manchester International Festival. The European Live Art Archive, coordinated by Girona University in Spain, and the prestigious Live Art prize presented annually at the ANTI – Contemporary Art Festival, Kuopio, Finland since 2014, along with opportunities to undertake Masters degrees in Live Art in both London and Helsinki, are further indicators that Live Art as a term and category of practice has international currency in institutional cultural contexts.

While we recognise that the catch-all term Live Art is problematic, we use it in this report to describe a sector of activity comprising, among other things, artists, organisations, spaces, policies, resources and audiences. Our approach to sectoral activity is indebted to sociologist Howard Becker’s examination of the complex networks of co-operative activity and conventions that help produce an ‘Art World’. 23 As such, while the focus of this report centres on a period of sectoral activity between September 2019 and May 2021, we draw throughout on earlier sectoral activity that helps bring the report period into focus. The report presents an indicative rather than definitive view of the sector and how it operates. It is intended to be read by artists, organisations, funders, policymakers and researchers in the Live Art sector and beyond with an interest in creativity, participation, social justice and diverse cultural practices – all key components of UK arts and culture funding strategies. It seeks to help generate new ways of thinking about how the sector works and enable further work, partnerships and research.

Part 2 forms the substantial component of this report on the UK Live Art sector, synthesising data from our surveys, case studies, focus groups, themed roundtables and dialogues, alongside desk research, to offer a snapshot of the sector. We begin in Section One with Key Structures, outlining the different types of infrastructure that support Live Art practices in the UK. Section Two on Creating and Making, examines how Live Art practitioners contextualise their work, and professional development journeys. In Section Three on Higher Education, we explore the close and mutually beneficial relationship between Live Art practices and higher education. Section Four on Audiences and Influence provides data, findings and case studies to demonstrate how the sector supports the distribution and visibility of Live Art practices. In Section Five on Demographics, we present snapshot data to illustrate who works in the UK Live Art sector. This is followed by Section Six on Diversity, where the focus is on Live Art’s work with disability, race and ethnicity, including discussion of the major Live Art UK project, Diverse Actions (2017–20). Section Seven on Sustaining and Organising presents survey data to indicate trends in livelihoods and organisational operations within the sector. In Section Eight on Post-March 2020 Conditions, we reflect on the ongoing and expected impacts of COVID-19 and Brexit, and how the Live Art sector is responding to renewed calls to address racial inequalities.

The Live Art Development Agency (LADA) is a centre for Live Art established in 1999, and a foundational resource for the advocacy, development and promotion of Live Art practices in the UK and internationally. Based at the Garrett Centre in Tower Hamlets, London since 2017, LADA champions experimental, interdisciplinary, challenging and unpredictable artistic processes. It works through curatorial projects, programmes, events, publications and a wide range of research resources and networks, including housing a comprehensive open-access archive of Live Art resources.

LADA’s achievements include major collaborations in publishing such as working with Intellect Books on Intellect Live, a series of publications about artists who work with Live Art (2013–20); artistic programming, including a collaboration with Tate Modern on Live Culture, a groundbreaking programme of performances, events and discussions by international practitioners (2003); professional development, including research bursaries for artists and the flagship DIY programme of professional development by artists for artists (2002–ongoing); artform development, for example Restock, Rethink, Reflect, a series of initiatives mapping and marking representations of identity politics in Live Art (2006–ongoing); and interventions in higher education, notably working with Queen Mary, University of London, to deliver and develop one of the first ever Masters-level programmes in Live Art (2018–ongoing).

At time of writing, LADA is undertaking a transformational process of organisational change and leadership succession, with co-founder Lois Keidan accelerating her process of stepping aside as Director to make space for new leadership in response to broader calls for racial equity within the arts and cultural sector.

Live Art UK is a membership network of promoters, facilitators and venues, concerned with the development and promotion of Live Art domestically and internationally. In 2019–20, Live Art UK had thirty members, reflecting representation across England’s regions and all nations except Northern Ireland. The network has grown substantially since its inception in 2003, more than tripling its membership. For a full list of membership please see Appendix II.

The Live Art UK network reflects the heterogeneous nature of infrastructure for Live Art in the UK. It comprises members of different scale, size and remit, including unincorporated artist-led initiatives, through to venues and funded organisations offering advocacy and artist development, internationally renowned festivals and key UK infrastructural organisations. Members of Live Art UK benefit from the ‘network effect’ of visibility, knowledge and resource sharing, and collaboratively developed initiatives.

Live Art UK is currently convened and administered by LADA. Membership is by invitation and proposal by existing members, based on the centrality of Live Art to a (potential) member’s purpose and activity, and their capacity to contribute to advocacy of the Live Art sector. At time of writing, network structure and operations are being reviewed.

The network cultivates opportunities for advocacy, including research into touring and writing about the artform, drawing out productive relationships between mainstream and experimental practices. It also functions as a conduit for lobbying and advocacy on sector-wide and policy level, undertaking advocacy on behalf of artists and organisations with an interest in Live Art. Our 2019 survey of individuals working with/in Live Art confirmed that Live Art UK is a productive resource for some individuals working in the sector, with 59% of respondents agreeing and strongly agreeing that it is important to have their work recognised by the network (Q15, SurvInd).

The Live Art UK network works together to identify key issues and opportunities within the sector and, where there is shared interest and motivation, the network develops collaborative projects to advance sectoral knowledge and experience. These have included gatherings with invited speakers, podcasts, symposia and publications on subjects including audiences and touring.24

Live Art UK’s project Diverse Actions (2017–20), was an example of a significant Live Art UK sectoral development initiative. Diverse Actions championed ‘culturally diverse’25 ambition, excellence and talent in Live Art, reflecting the sector’s concern about the historic lack of racial equity in relation to artist and leadership development. Funded by a £500,000 Arts Council England Ambition for Excellence Grant in 2017 with cash and in-kind contributions from Live Art UK members, this was the largest investment in the Live Art UK network since its beginnings. While the sector reported that there were many positive outcomes from this project, Diverse Actions has also raised a number of issues and challenges, which are discussed later in Part 2, Section Six, entitled Diversity.

Our research has identified the importance of artist-led initiatives to the sector, and not only in terms of their contribution to sectoral activity. Artist-led initiatives contribute to the way those working with Live Art often imagine their practices and process as anti-institutional. Artist-led initiatives across the regions and nations of the UK have made and continue to make an important contribution to the creation, development and support of practices, artists and arts workers in the Live Art sector. According to our 2019 survey of individuals, 75% of 225 responses either agree or strongly agree with the statement ‘Artist-led initiatives are important to my Live Art practice’ (Q20, SurvInd).

In this research, we refer to ‘artist-led initiatives’ as self-organised and collective activity, which may be led by artists, independent producers, curators or other categories of practitioner working with Live Art. Although artist-led initiatives are self-organised and collective activities, these initiatives do not necessarily adopt co-operative organising structures or co-operative economic models, as we will see in Part 2, Section Seven, on Sustaining and Organising.

Artist-led initiatives are essential to driving the development of Live Art practice because they are informed by on-the-ground knowledge and the needs of their communities of practice. Artist-led initiatives have grown ways for artists to work outside the parameters given by funders and institutions, allowing for experimentation and the development of communities that, in many cases, foreground resistance to formal structures, administration associated with public subsidy and/or views of arts management as supplementary to creative practice. For instance, the artist-activist home-based initiative, Institute for the Art and Practice of Dissent at Home in Everton, developed in response to artists being appropriated by the 2018 European Capital of Culture in Liverpool.26 Another example of an artist-led initiative is the artist-led community Residence, who joined forces with other artist-initiatives to create an important social performance space at the Brunswick Club for artists working in Bristol. Fox Irving’s research into class and navigating the art world led to the conception of the peer mentoring group Women Working Class, and the development of a range of resources for artists and producers in the sector and beyond.

At the same time, artist-run activities across the arts and cultural sector have often historically relied on wider economic and social contexts and policies for their appearance. For example, Thatcher’s Enterprise Allowance Scheme benefitted DIY cultural production 27 in 1980s Britain28.

In the UK Live Art sector, artist-run initiatives also frequently draw on knowledge, personnel or resources from more formal sectoral institutions and affiliations. For example, LADA manages and facilitates DIY, a programme of professional development projects by artists for artists – an important artist-centred initiative that has been running since 2002, working with (at time of writing) more than 20 partners across the UK. Similarly, BUZZCUT, an important artist-led initiative that began in Glasgow in 2012, has transitioned over recent years into a partnership with the major experimental festival Take Me Somewhere, including sharing staff and ‘backroom’ operational resources. Some artist-led initiatives, such as Chisenhale Dance Space have, over time, developed to become key organisations and initiatives for the sector.

According to our research consultations, individuals and organisations working within the Live Art sector have been deeply impacted by the wider pressures of austerity and the rising costs of living in the UK, resulting in decreased capacities to sustain and undertake grassroots activity. As is evidenced throughout this report, artist-led initiatives often rely on unpaid or underpaid labour and informal sharing networks to create and deliver their activities.

Facing an accelerated professionalisation and simultaneous shrinking of resources for artist-led activities in the UK, we note the emergence of a number of support networks led by practitioners working collectively and collaboratively with Live Art developing over recent years.29 For instance, Asia-Art-Activism is a network of artists, curators and practitioners focused on celebrating and sustaining marginalised artists’ practices.

We note through our research consultations that artist-led initiatives, particularly in non-urban locations, are hyperlocal, in that they take place within specific localities. These are often undocumented outside those localities, yet play a role in the incubation and development of Live Art practices. Although it is beyond the scope of this project to document these, further research into non-urban artist-led initiatives could be of value to the sector.

What are the models for consuming Live Art? The focus on festivals means it is not accessible all year round.

Focus group participant, 2019.

Festivals

Our research has identified festivals as a primary mechanism for the presentation of Live Art in the UK. Festivals can often provide flexible frames for the presentation of artworks that include non-traditional uses of space and time, like site-responsive, participatory and durational work. However, as noted above, the centrality of festivals to the UK Live Art sector is not without challenges for artist and audience development, particularly in areas of the UK where year-around infrastructural support for Live Art is limited.

Nevertheless, Live Art festivals such as In Between Time (South West), Fierce (Midlands), Compass (Yorkshire), SPILL (East of England), Catalyst Arts’ FIX (Northern Ireland) and Forest Fringe’s Edinburgh programme (2007-2017), illustrate that festivals are a robust focal point for audiences, reaching wider publics and connecting artists and organisations within a community of practice. Also, festivals like London International Festival of Theatre, Manchester International Festival, Brighton Festival and the London International Mime Festival are mainstream settings that play an important role in the commissioning and presentation of large-scale and international work.

Festivals are part of a nuanced ecology of local, regional and national Live Art organisations and initiatives across the UK, where partnerships in the form of co-commissioning, co-production, artist development and more informal support structures help sustain and feed into the presentation of work on a range of festival ‘stages’.

Many venues that present Live Art have a wider arts programme and remit, therefore festivals enable focused activity on Live Art, providing vital opportunities for practitioners and audiences to gather and experience work. In addition, festivals offer artists vital opportunities to profile their work, to see work by others, engage in dialogue and conversation sessions, as well as more informal networking activities including meeting organisations and promoters. Festivals such as Experimentica at Chapter, Cardiff and NOW festival at The Yard, London take place within larger art centres and theatre programmes respectively. Transform in Leeds, Gateshead International Festival of Theatre (GIFT) and Knotty in Folkestone are examples of festivals that are commissioning artists working with Live Art to work site-responsively, offering opportunities for audiences to experience Live Art practices that reimagine place. Using varied audience engagement activities in diverse settings, Live Art festivals contribute to creativity within their local communities.

Clubs and corner shops

Through partnerships and collaborations, the Live Art sector enables advocacy, dialogue and resources for Live Art practitioners to work within various settings and with/in communities. From performances at queer clubs like VfD in East London to Bbeyond’s interventions in public spaces in Belfast, to projects in community centres and extra-care facilities, Live Art has built a reputation for inhabiting heterogenous, non-traditional spaces.

Artists working with Live Art in non-traditional spaces have also pushed the boundaries of where participation in the arts might take place, making Live Art practices accessible across the UK. Joshua Sofaer’s Opera Helps sends professional opera singers to private homes in response to individual audience members asking for help with personal problems. In Woodland, French & Mottershead bring audiences to the woods to connect with deep time and chemical and biological processes. Cruising for Art, created by Brian Lobel, asks audiences to use gay cruising codes to engage in intimate interactions with performers.

Working outside traditional arts and cultural spaces is partly out of necessity. As we have noted in Part 1, Section Three: Addressing the term ‘Live Art’, Live Art practitioners often challenge social and cultural norms, which has not always been welcome or supported in mainstream arts and cultural spaces. Moreover, the varied forms and durations of Live Art practices often challenge curatorial approaches, working structures and technical resources, especially for spaces that are aligned to non-Live Art specific artistic disciplines and histories. This is further discussed in Part 2, Section Two: Creating and Making, and in relation to touring, Part 2, Section Four: Audiences and Influence.

Arts and cultural institutions/spaces

We recognise from research conversations that dedicated space for the making and presentation of Live Art is an important intention of the sector. Historically, access to free and low-cost spaces has been more readily available, and even a large space like Shunt Vaults in London was a hub for encountering artists working with Live Art. Today, we see the impact that the multiple challenges posed by austerity and increasing property costs have had on securing dedicated spaces for the presentation of Live Art in the UK. Of the few notable spaces dedicated to Live Art, the majority of these are artist-led, including ]performance s p a c e [ in Folkestone and its sister space VSSL in London, and Centre for Live Art Yorkshire (CLAY) in Leeds.

Moreover, Live Art has occupied spaces outside dedicated Live Art contexts ranging from music festivals such as Latitude, to multi-artform festivals – like Glasgow International and Norfolk and Norwich Festival – main stages of theatres such as the Royal Court Theatre and public programmes at galleries and museums including Baltic, Victoria and Albert Museum and the De La Warr Pavilion. Our research consultations inform us that artists working with Live Art experience developmental benefits from working outside Live Art specific contexts, learn from adjacent artistic disciplines, value exposure to different audiences, and can benefit from an expanded profile.

Platforms

Our research conversations indicate that artists and practitioners value the function of platforms as an essential part of the Live Art sector’s infrastructure. The term ‘platform’ is used in different ways across the sector, but usually offers artists and audiences the opportunity to experience short works by multiple artists as part of one event. Platforms can function in different ways: some can help an artist build a continued relationship with an organisation, whilst others are showcasing opportunities in their own rights. Home for Waifs and Strays in the Midlands and SPILL YER TEA in Liverpool offered artists informal, peer-centred opportunities to regularly try out new work and work in progress.

Other platforms are more formal and are structured as part of a facilitated developmental process, often feeding into an artists’ wider professional and creative development journey. An example of this is the Starting Blocks Showcase at Camden People’s Theatre in London, which is the culmination of a 10-week artist residency. Flying Solo at Contact in Manchester is unusual and therefore significant in providing a platform for solo practitioners to develop and present their work. Perhaps one of the most notable national platforms for Live Art is organised by SPILL and plays a key part in SPILL festival.

The digital

Digital offers much opportunity for the development, sharing and presentation of Live Art practice. Digital platforms such as LADA’s Live Online, are a vital part of the Live Art ecology in the UK, with their usage becoming inevitably more widespread, especially due to social distancing restrictions since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. From our research, artists and organisations in the UK who work with Live Art, such as the artist collectives Blast Theory and Lundahl and Seitl, have a long history of engaging with digital practice. Responses from our 2021 organisational questionnaire, inform us that digital is understood by the UK Live Art sector as an arena for disseminating and publishing Live Art. Digital plays an important role in distributing practices to audiences where the means to experience Live Art in person are limited by location, access or mobility.

While the presentation of Live Art via online spaces can have implications for the audience’s experience of ‘liveness’ and the physical encounter, digital also offers wide-ranging possibilities for artform development, such as seeding new forms of encounter with audience members that can inform other artforms and disciplines. Digital also affords practitioners working with Live Art opportunities for remote partnerships and collaborations. Indeed, through our research consultations, organisations such as the British Council have noted high levels of interest in digital collaborative projects and digital international residencies from artists working with Live Art, particularly since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Artists and organisations working with Live Art in the UK are primarily supported through public funding, involving grants from local councils, Arts Councils from across the nations, the National Lottery Community Fund and international funders such as European Cultural Foundation and/or national cultural institutes such as the Goethe-Institut. As discussed throughout this report, trusts and foundations such as Jerwood Arts, Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, Paul Hamlyn Foundation and the Wellcome Collection also play a significant role in the funding of Live Art practices.

In addition, the UK Live Art sector is subsidised through the free labour of individuals participating in its activities, which is reflective of labour trends within the arts and cultural sector more broadly. Resilient yet underfunded, our research indicates that artists and organisations often over-promise on delivery to demonstrate value to funders and over-work to meet these demands. Self-subsidy through unpaid or underpaid labour negatively impacts the health and wellbeing of individuals involved in the Live Art sector and the sustainability of the sector’s initiatives and organisations. Sources of funding and income within the Live Art sector are further illustrated and discussed in Part 2, Section Seven, on Sustaining and Organising.

A. Processes and contexts

Live Art has allowed me other logics of worlding, more liveable ones

Respondent, 2019 survey of individuals

Live Art has been a safe space for allowing hybridity of form into my practice, venturing into areas that I might otherwise have felt too unskilled or daunted to go into. My practice has been programmed in many Live Art events, as well as other contexts that were less focused on Live Art. As a programmer I have worked to develop the exchange and conversation between dance and Live Art especially. In my teaching, I focus on Live Art and invite students to engage with Live Art as a practice.

Respondent, 2019 survey of individuals

Live Art invites artists, arts organisations and those they encounter and work with to embrace complexity and different perspectives. The expansive and wide-ranging set of practices that are collected under the umbrella of Live Art cut across a variety of artforms that celebrate diverse methods and processes of making, from the messy to the risky, the spectacular and the everyday. At the same time, Live Art involves consideration, development and advancement of methodologies and rigour, drawing richly from other artforms as well as disciplines beyond the realms of arts and culture. Despite its history as a contested term, findings from our 2019 survey of individuals show that the term ‘Live Art’ has traction, with 69% of the 258 respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement ‘Live Art as a term and/or practice informs me as a creative person’ (Q4, SurvInd).

Practitioners working with Live Art have strong associations with other artistic disciplines, identifying with a range of artforms and disciplines based on artform categories designated by Arts Council England. Early in our research, in consultation with our 2019 Artist Perspectives Roundtable, the category of ‘performance’ was added to the list of artforms/disciplines, informing design of our 2019 survey of individuals. Our research finds that ‘performance’ and ‘experimental performance’ are by and large the most resonant of terms to describe these practices. From our 2019 survey of individuals, we see that 94% of 258 respondents identify with the term performance (Q2, SurvInd).

I’ve produced several events platforming Live Art, allowing us to activate a public space in a new way and by extension reach new audiences. These sites include a council-owned playground, a nightclub, and church building. I’d like to think my practice as a producer has also facilitated experimentation with emerging artists using live elements in their practice and embedded meaningful live engagement into impact strategies.

Respondent, 2019 survey of individuals

Our research indicates that the Live Art sector in the UK nurtures a broad spectrum of ideas and practices. Through our desk research, survey and research conversations, and particularly by considering first-hand accounts, we note that practitioners who engage with Live Art are attracted to the openness to diverse creative approaches and cultural practices that Live Art as a cultural strategy offers.

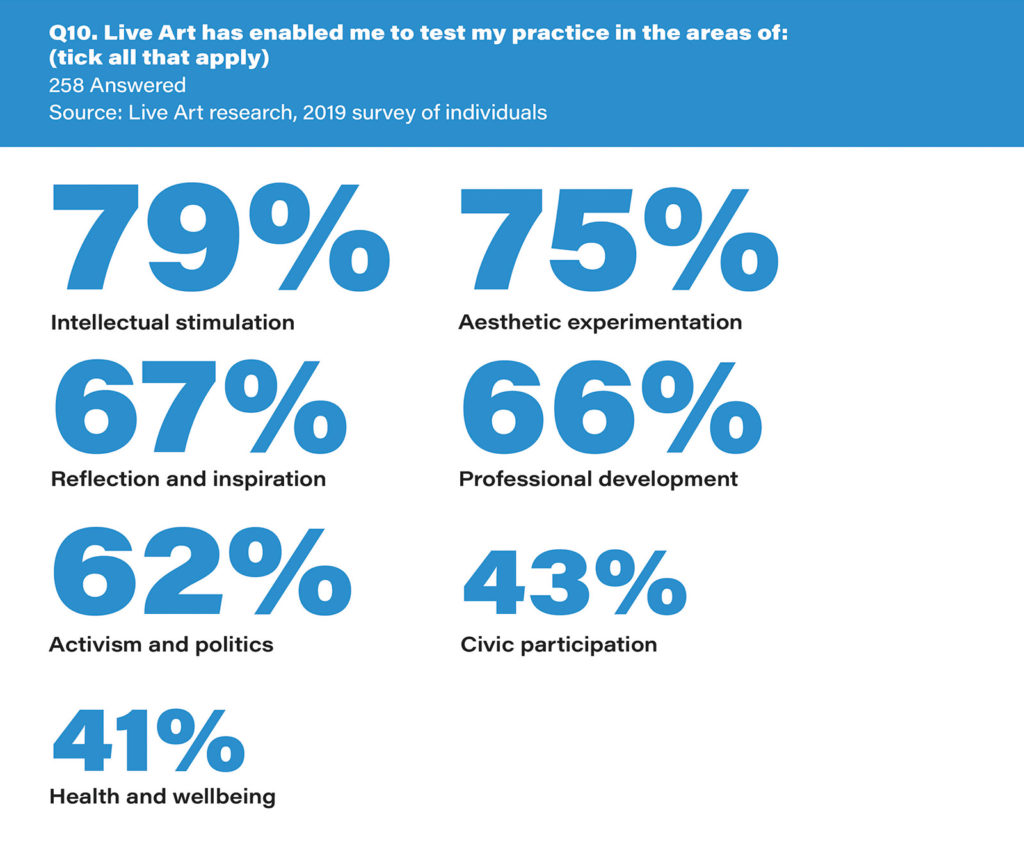

We note that Live Art’s embrace of rigorous, process-led approaches into how artistic and cultural practices develop, rather than an emphasis on a finished product, was valued by participants in our research. This appears to engender a receptiveness to new ideas, a development of aesthetic and professional practice and encourages investigation into other social spheres. 73% of the 258 respondents to our 2019 survey of individuals agree or strongly agree with the statement ‘Live Art has enabled me to test my practice in a number of different areas’ (Q9, SurvInd). Thinking about that statement, respondents were then invited to tick as many options as they felt relevant (Q10, SurvInd). 258 respondents answered as follows:

Deploying a broad spectrum of skills, methods and knowledge, including improvisation, movement, choreography, participatory research, dialogue, sound, writing, photography, and moving image, artists working with Live Art draw on different types of physical resource and facility depending on the intentions and needs of their project or process. Whilst some may place value on making time alone in the rehearsal studio, others work collaboratively or collectively with members of the public, or in non-art environments. As is seen by the 75% of respondents who stated that Live Art enables them to test their practice in relation to aesthetic experimentation, being inspired by new ideas and experimenting with them is critical to those working with Live Art.

Working outside Live Art specific contexts, such as galleries or multi-artform festivals, is not without challenge. Live Art can include working site-responsively, in collaboration with non-arts professionals or producing outcomes in a number of different media. Depending on artists’ distinct ways of working and the remit of the project, the development of Live Art often requires dialogue and collaboration between artist and curator, in order to realise the artists’ vision.

Live Art practice has allowed me to consider the ways and means by which we support the creation of new work differently, to properly consider the space and time that requires, the intelligence and depth of thought and listening that live artists require from curators and their curation as part of multi-artform programming and given a sense of permission to engage and play with audiences and their perception and the disruption of their everyday in new ways.

Respondent, 2019 survey of individuals

Through research conversations with programmers and curators whose primary work is outside Live Art, it has been noted that the process of gaining knowledge about how to work flexibly and responsively with Live Art practitioners takes time and resource. The success of a complex Live Art project requires internal advocacy from key staff within the presenting organisation and an understanding and involvement in the process of making, not only from the technical and producing staff but also the fundraising and front of house teams.

67% percent of the 225 respondents to the 2019 survey of individuals indicated that their work with Live Art has led them to work with organisations outside the arts sector (Q23, SurvInd). We note from our research that artists working with Live Art are active collaborators, working with practitioners from other sectors, as well as being multi-disciplinary when it comes to artform practice.

Through a synthesis of our research materials, what appears specific about the character of collaboration is how artists working with Live Art foreground a critical and yet creatively open approach to the live encounter and to the relationship between bodies, histories and spaces. Work such as jamie lewis hadley’s collaboration with Vishy Mahadevan, Professor of Anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons, on the history of medicinal bloodletting (funded by the Wellcome Trust), or Barby Asante convening forums for locally-recruited womxn of colour to share experiences in relation to colonialism in the project Declaration of Independence, are indicative of the hybridity of collaborative work supported by the Live Art sector. Practice which enables collaboration across artforms and across sectors is a key feature for those working with Live Art.

B. Creative and professional development

Creative and professional development is a principal activity of the Live Art sector in the UK. Professional development activity in Live Art aims to create opportunities for artists to experiment, spend time working on new ideas, learn new skills, share experiences, meet one another, feel more connected and build solidarity. As discussed in Part 2, Section One: Key Structures and outlined above in ‘Processes and contexts’, artists working with Live Art often lead the way in identifying the kinds of creative and professional development they need, reflecting that there is no fixed, singular way of developing a Live Art practice.

According to our 2019 survey of individuals, 64% of respondents said they had participated in and/or organised professional development programmes for Live Art practitioners (Q17, SurvInd).30 The rich seam of platforms, showcases and development opportunities within the Live Art sector informs, builds and contributes to a community of Live Art practitioners. The development of those that work in the sector and the development of the sector itself is linked.

Arguably, a significant operation of the sector, creative and professional development – for example, through Live Art UK initiatives – equates to support for the development of artists and other practitioners. However, since opportunities are frequently highly competitive, with applications time-consuming and often restricted to artists of a certain age or those who have been practicing for a specific number of years, many artists are not able to benefit from meaningful sustained support.

Many people are working right across the country but can’t afford to go to things, even if they are free, as they have no money to get to London… There are also additional barriers in terms of childcare.

Focus group participant, 2019

The above quote illustrates findings from our research on barriers to sector participation. Such perspectives are echoed by wider research on the arts and cultural sector. For instance, a report from TBR on artists’ livelihoods, distributed by partners including the Live Art Development Agency, notes that factors such as finances, geography and class pose barriers to artists engaging with creative and professional development opportunities.31 Furthermore, the TBR research affirms that whilst there are instances of successful artist developmental trajectories, career ‘progression’ is often non-linear. Non-linear career progression may be embraced by some practitioners, however, our research consultations evidence that lack of financial stability and linear career prospects particularly affect artists and practitioners working with Live Art as they age, often influencing their decision to leave the sector.

Programmes, including bursaries:

Many organisations working with Live Art offer opportunities for the development of artistic practice including opportunities to research, share approaches, exchange ideas and get feedback on work in development. Activities vary in budgetary support, duration, form and methodology. Some development opportunities come with financial and other in-kind support, for example both Artsadmin’s Artists’ Bursary Scheme (1998–ongoing) and the Katherine Araniello Bursary (2020–ongoing)32 offer open-ended opportunities for artists to define their needs and next steps. hÅb’s numerous artist development programmes and platforms include Divergency (in collaboration with Sustained Theatre Up North), which supports a weekly gathering of artists.

Residencies: These can focus on supporting research in relation to an artist’s practice or centre on making a specific piece of work. As is the case in the arts sector as a whole, residencies may include studio access, a stipend and/or contribution to material costs, whilst others may be unpaid but offer free studio access or require the practitioner to pay a subsidised rate to access space. Through our research consultations, we found that residencies are especially valuable to artists where the cost of making or rehearsal space is often unaffordable, especially within urban centres.

Several schemes have presentation opportunities built in, including Compass Live Art’s artist residencies, which span two weeks to one year; Nuffield Residency, Lancaster Arts; and Cambridge Junction. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, digital residencies have become increasingly important for practitioners, a notable instance of which is produced by performingborders. Residences also offer artists the opportunity to build relationships with organisations who may be able to support or present their work in the future.

Mentoring: Our research has identified that mentoring is an important activity for artists and workers in the sector, with more than half of the respondents to our 2019 survey of individuals stating that they offer unpaid peer mentoring to other practitioners within the sector (Q36, SurvInd). For artists who do not have regular access to studio or devising space, and those who do not have a producer, mentoring can provide a system of structured exchange and an important opportunity of discourse and dialogue for artists to talk through how they are imagining a work. Artists very much value the knowledge and experience of other artists to give creative feedback and help them to solve problems, making mentoring a significant part of creative and professional development within the Live Art sector.

Organisations within the sector are increasingly offering open access advice sessions to artists, and some artist development programmes also include mentoring provision. Other areas of advice and support include helping with grants and applications, and creative dialogue to support the development of a work at different stages.

Developing producers and curators: The sector has identified a need to support the development of producers and curators. This has mainly taken place as on-the-job training through opportunities with festivals, including the South West-based festival In Between Time. In 2020, the festival Block Universe worked with an emerging curator and ran a paid trainee scheme for two individuals in collaboration with the Art Fund to develop event production, curatorial and audience engagement skills. Another notable opportunity has been the Artsadmin 9-month trainee scheme which has been restructured as a 3-month Producer Fellowship (2021 onwards). Whilst traineeships and internships are a well-established mechanism for developing producers and curators, if not well-managed and resourced they can reproduce the unequal working conditions which have historically been found in the arts and cultural sector more broadly.33

There is an increasing recognition of the need for continued professional development that is tailored to producers, working in organisations and independently, at different stages of their careers and for different experience levels. For instance, Producer Farm, co-produced by In Between Time, Dance Umbrella, Bristol Old Vic FERMENT, Fuel and Coombe Farm Studios; Producer Gathering, organised in collaboration with Marlborough Productions; and The Uncultured’s producer mentoring scheme all aim to address the clear need for development opportunities for producers. As well, the British Council’s Generate scheme, a partnership with Arts Council England, has enabled a new network of international collaborations between UK and US producers.

Developing writers and critics: The sector has also identified the need for the development of practitioners who can write about Live Art practice. The prevalence of first-person narrative in writing about Live Art reflects the importance of embodied experience; it is practiced as a live form. Writing about Live Art is key to how Live Art is transmitted, how Live Art is able to feed into other practices and how Live Art is archived and historicised. Writing from and about Live Art is also central to audience development. We note from our consultations that there is a desire from artists, audiences and organisations working with Live Art to encounter more writing about Live Art that is not academic and more accessible to a wider readership.

Live Art UK’s project Writing from Live Art (2006) made a significant contribution to the documentation, contextualisation and artistic impact of Live Art. Other initiatives for developing writers and critics taking place in the sector have often been associated with festivals or wider programmes, including Critical Interruptions’ Live Writing projects in collaboration with Steakhouse Live festival (2016) and the Diverse Actions writing workshop, in collaboration with Compass Live Art festival (2018).

Access to opportunities: Currently, sector provision for information about opportunities centre around a small number of listing services, including Artsadmin’s e-digest email newsletter, circulating to more than 12,000 subscribers. Social media is also increasingly important to artists and practitioners working with/in Live Art to learn about resources, learning programmes and opportunities.

Staying informed and sharing practice

Professional platforms are key to staying informed, sharing practice, developing learning, creating connections and strengthening networks. Participants in our 2019 survey of individuals and in our consultations note that attendance at nationally recognised festivals and showcase events are key networking opportunities and often contribute to further commissions or work.

Throughout our research consultations, the sector has remarked on the thinning out of developmental platform events across the UK. Limited opportunities and barriers to networking and meeting other practitioners including promoters, programmers, curators and producers within the UK was also noted. The sector reported that these challenges impacted practitioners’ capacities to raise visibility of their practice and further their work beyond a local or regional level. Those living in non-urban settings or where there is little sectoral infrastructure for Live Art reported this was a particularly acute issue.

Despite the importance of professional development opportunities to artists, practitioners and organisations within the sector, we note through our consultations and survey of individuals that there remain numerous barriers to accessing development programmes. These barriers include:

We note that informal, self-organised and peer-to-peer professional development activities, such as mentoring, are central to the health of the sector although often under-acknowledged and under-resourced. This is further evidenced in Part 2, Section Seven, on Sustaining and Organising.

Our research emphasised that the intersection between Live Art and higher education departments in Theatre and Performance and Fine Art is extremely significant. Through our consultation process and in our 2019 survey of individuals, participants expressed the importance, value and high stakes of the relationship between the sector and higher education, from articulating Live Art as an artistic practice and art historical category to professional development and workforce cross-subsidy.

The development of the UK Live Art sector was linked through policy to higher education from its inception, with the Arts Council in London making engagement with higher education a condition of funding for a new development agency for Live Art in 1999.34 At the time, other than a few institutions such as Dartington College of Arts, Nottingham Trent University, the University of Ulster and Cardiff School of Art and Design, there was little sustained provision for non-mainstream experimental performance-based practices. Specifically, there was a lack of provision for emerging artists and arts workers working with Live Art in London. Addressing the need in London became part of the initial scope for establishing the Live Art Development Agency (LADA).